“’The film is really not just the story of this amazing woman and her transgressive and adventurous and reinvented life. The story is really a film about the politics of national memory because what I found is that she had literally been erased. What she said about the Civil War and what she had done during the war was dangerous to the Southern myth makers post-Civil War, and that’s why her story isn’t known today.’” (Quoting Maria Carter)

Kino-Eye (Blog)

By David Tames

KINO EYE

May 24, 2013

By David Tames

Maria Agui Carter talks about “Rebel,” a documentary about Loreta Velazquez

Rebel: Loreta Velazquez, secret soldier of the American Civil War is a new documentary by María Agui Carter that tells the story of a woman who has been shrouded in mystery and the subject of debate for many years. Her story is one of the most gripping narratives of the Civil War. While the U.S. military may have recently lifted the ban on women in combat, Loreta Janeta Velazquez, a Cuban immigrant from New Orleans, was fighting in battle 150 years ago. Who was she? Why did she fight? And why was she virtually erased from history? María Agui Carter brings to life the story Loreta Velazquez as a woman, soldier, myth, and a vehicle through which we can

better understand the politics of national memory. I recently sat down with Maria to talk about her film and the journey making it. Rebel will have its broadcast premiere

tonight on PBS.

David Tamés: When did you first become interested in the story of Loreta Velazquez?

María Agui Carter: I had heard the story around the year 2000 and that it was perhaps fictional. Although it was fascinating to think of this transgressive character, a woman who dares to dress up as a man in 19th century America and goes off and fights for the South in Civil War battles and then becomes a spy and then switches sides and becomes a spy for the North, it didn’t seem like it was a story for me because I love documentary filmmaking.

Obviously you ended up making a film about Velazquez, what changed for you?

The story continued to fascinate me and I continued to read about women soldiers throughout history, not just in the Civil War. A couple of years later I came across They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War by De Anne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook. They wrote about the women soldiers of the American Civil War, estimating that as many a thousand women fought in the war.

I’ve been a great fan of Ken Burns’ Civil War series, which I thought was fantastic storytelling. He doesn’t approach films the way I approach documentary, but he and his team are really brilliant storytellers. And there was never once in all those many hours of Civil War stories any mention of women soldiers. And yet I thought this was newsworthy just because of the Victorian period in which they lived.

And so I called up DeAnne Blanton and said, “why do you talk about these women soldiers, including Loreta Velazquez, as real people? Do you have documentation?” And she said, “next time you’re in D.C. come and visit me.”

So I did, and she started pulling out all these documents about women soldiers of the American Civil War, including documentation about Loreta Velazquez. At that point I got really excited about the stories of the women soldiers and Velazquez because she had written The Woman in Battle, her own first-person memoir. So I felt there was material on which to hang a documentary. But I needed something else, and that something else was my question about why we didn’t know about this amazing woman.

The film is really not just the story of this amazing woman and her transgressive and adventurous and reinvented life. The story is really a film about the politics of national memory because what I found is that she had literally been erased. What she said about the Civil War and what she had done during the war was dangerous to the Southern myth makers post-Civil War, and that’s why her story isn’t known today.

Your first impression of Velazquez was that her story was fictional. Why would you assume it was fictional?

First, because it seemed astonishing to me that with so much literature around the Civil War (it’s almost like Bible stories) that it seemed impossible to me that with all that material, that the stories of these women soldiers would not have come out, especially because Loreta’s memoir is one of only two memoirs published by a Latina in the U.S. in the 19th century.

And so given all the contemporary movement to recover Latino literary history, it seemed to me that this must not be true. That’s why we don’t know about it. When I read articles about the women soldiers, the historical literature referred to them as either insane or prostitutes so that there was a historic illusion to dismiss their stories or erase them.

What do you think was behind that? Was it just a general disregard for the role of women in the Civil War, or was there a concerted effort on somebody’s part?

What we find is that during and after the Civil War, the women who had fought with the soldiers and who had maintained their secrecy, once they were found out, often times the veterans would support them and there were many letters, mentions of these women, that their bodies were found on the battlefield, they showed up in newspaper articles. So while veterans were alive and while that story was still fresh in people’s minds, it actually circulated quite widely.

It’s not until veterans started dying and people started looking back and ideas of Freudian sexuality and the sort of more professional historians started looking backwards with a gender lens during a period where women were still not considered people who should be on the war front fighting as men that their stories began to be questioned.

Some of the historical material I read would mention women soldiers and they would disparage some of these women who dressed up as men as camp followers, which was another way to say they were prostitutes. Or there were some women who had picked up a rifle, but they were just following their husband and then they went home.

A lot of what happened centers around Jubal A. Early who was the head of the Southern Historical Society post-Civil War, he was an ex-Confederate general who was an attorney and ended up having a lot of time on his hands because for years he was the representative of the Louisiana lottery, which was basically a scam where they would promise that somebody would win, but nobody would ever win. They were kind of the Enron of their day. So they would pay him a huge amount of money to come once a year to Louisiana and pull the numbers and say “the Louisiana lottery is on the up and up.” And so he had the time do whatever he wanted, and he said “we may not have won the war with the sword, but we will win it with the pen.”

He wanted to restore the honor and myth of that “Gone With the Wind” mythical South full of honor and good intentions. He wanted everyone to believe that the war was not about slavery, but by the way, he also believed that slavery was actually good for those “savage Africans” because they couldn’t live on their own, and furthermore he believed they were actually made by God to be different and subservient and inferior to the white race.

And this myth making became the most important thing, and he became the president of the Southern Historical Society, which was the publisher of many memoirs and histories of the American South. He wrote the first memoir as a veteran of the Civil War. People would send their memoirs to him, and then he would red-line them, edit them, and say, “oh, no. No. No. It was like this, it was like this.” And no one dared cross him. He was known to destroy reputations, and famously, he destroyed the reputation of General Longstreet, also a hero of the Confederacy, but by the time Jubal Early was done with him, he was a pariah throughout the South.

What was Jubal Early’s reaction to Loreta’s memoir?

Jubal Early came across Loreta’s memoir in 1878, two years after she wrote it. She was a very minor character to him, so he did not launch a concerted effort against her. All he had to do was write a letter here and there and speak out against her, but he was so powerful and well known and respected. If the famous Jubal Early, historian of the Confederacy, almost official historian of the South and the Southern Historical Society, said this woman was a hoax, she must be a hoax, his influence was enough to sway many other people. I think that was the beginning.

Was there ever any direct interaction between Loreta Velazquez and Jubal Early?

There was. She found out that he was speaking out against her, and she wrote to him. He refused to write her back, and she actually went and visited him. We have a record that she visited him in a hotel in Lynchburg, Virginia where he lived and there was a short meeting. We don’t have a full account of what happened, but clearly she was not successful in convincing him. Afterwards he said that she didn’t speak with a Spanish accent. Therefore, he was sure she couldn’t have been a Spanish lady.

Loreta was a Cuban immigrant who arrived when she was seven. So just like I arrived when I was seven and speak English without a discernible Spanish accent, most children would speak perfectly, if they came here that young. So his assertion that she couldn’t have been Spanish because she spoke English properly was ridiculous. He accused her of being a prostitute basically and said that’s why she would have known about camp life.

Early said there were no women in the armies of the Civil War, although he himself had two women under his command who were found out and kicked out of the army. With a swat of his hand, he dismissed her quite easily. That’s all he had to do.

Your film involves a lot of historical research, and you have scholars in your film who help tell the story. What was the experience of working

with scholars like and trying to balance between the demands of storytelling and the demands of historical accuracy? There’s something very

different about Rebel in that it seems solidly grounded in history and yet it’s compelling storytelling. Often those are at odds with each other, but

they don’t seem to be at odds in your film.

I’ve made documentaries for twenty years now, and when I first began, I began in vérité documentary, which I love. And over the years I’ve changed my approach to working with interviews and scholars. There’s always an element of surprise in an interview, and you don’t always know where you’re going. And yet as a documentarian, as a person who has done their research and is conscientious, you always come with a set of questions. So one of the things that really helps with a great interview is to be able to truly listen to what someone is telling you and follow up on that, rather than sticking to your script of questions.

But there’s another thing that I’ve changed over time in my approach to doing interviews, in my early documentaries I used a vérité approach, I would shoot and shoot and shoot and find the story in the footage over time, find it in the editing room. With a historical film you can research and research and research and find a shape to your story before you actually shoot it. And indeed that’s what I did using her memoir and using the documents about this story before I actually started shooting. I read the work of the scholars, and I wanted stories from them, not just the facts, those are two different things.

How do you reconcile historical facts and good stories?

I approached the interview questions in a different way than I had approached them in previous work. I tried to put them in almost conversational contemporary terms where I was asking someone to tell me about this story not as a scholar, not as an academic, but as a person, perhaps sitting at a cocktail party. And this is the story I would tell my interviewees before we started.

Imagine that you’ve entered a cocktail party and that you’re standing in front of the buffet and the drinks. Those are behind you, and the person has just come up to you and asked you what you’re doing. And you want to tell them about Loreta’s story, but what they really want is to get to the buffet and the drinks behind you. What is it that is so important about Loreta and her story that you would tell in this context? But I’m not going to ask you just in a general way. I’m going to ask you very specific questions. And when I ask questions, I would ask them to tell me episodes and stories rather than analysis.

The other thing I did is that I kept in contact with the scholars over time so that I would read something, call them up, have a chat, check in with them a month later and talk with them. By the time we actually met, we were almost old friends, having talked about issues around the context of her story for a very long time before we actually sitting down for the interview.

You have to be careful because you don’t want the freshness of what they’re saying to disappear in voluminous conversation before the interview, but I gained the trust from these scholars because they knew that I had done my research and that I had read their work beforehand. So there was a level of intimacy and trust that we were able to establish way before actually turning on the camera and meeting in person.

The scholars were also my guides, and I asked them for their opinions along the way. I sent early scripts to some of my scholar advisors and got feedback from them because I wanted to know that the context in which I was putting Loreta’s story actually made sense to them. I could never hope to be as much of an expert as each of the scholars are. Being able to check in with all these people throughout the project provided a brain trust.

We also had very clear parameters that after I showed those early scripts, I would listen, but I would make my own decisions based on filmmaking needs that are not always the same as academic or scholarly needs. And so after those early scripts I stopped sending my cuts to them because at that point it was about telling the story, not necessarily just telling the content.

So you started with a foundation based on the scholarly research, and from that interaction, a story emerged. Were there any surprises about

Loreta’s life you discovered while making this film?

It was a very difficult film to edit, and the biggest tension was a 19th century story about a woman from a community that is not known to people and a history that is not known. Not that Civil War history isn’t known, but the connection between Cuba and the American Civil War, the connection between Havana and New Orleans and the 19th century community of Hispanics in the U.S., the South and the West, is unknown. And so there was a constant tension between how much history do I tell so that her actions are understandable within a larger historical context.

That’s really tricky, and what I found is that although I know that people don’t understand this deep, deep history, I had to go beyond using words in my storytelling, and I had to tell that context in image and in editing and in other ways. For example, one of the things I was trying to convey about 19th century Hispanics and Spanish and Cubans—Latino and Hispanics are contemporary terms that they would not have understood in the 19th century—is that they’re white but they’re not white but they are this liminal subject between black and white and that there are these underlying race issues that are not always explicit but that drive some of their actions.

For Loreta, I understood in her memoir that she’s constantly trying to prove and intimate whiteness. And so you might read that and say, well, she considers herself white. But when you understand the history of Hispanics in the 19th century in the U.S., just after 1848 when for the first time there’s been massive contact between North America and the Latin world in a war context and she’s sitting in New Orleans as a child having recently arrived and New Orleans is both a center of war press and staging area for the U.S.-Mexican War.

Then you understand that she’s in an environment with an intense amount of hatred and hate mongering happening all around her against Mexicans and more largely against people of Spanish descent because Mexico has been a colony of Spain. And she is also from Cuba, which is also a colony of Spain. And so she is seeing all around her a hatred towards people of Hispanic descent.

You must understand that when you understand her character, and yet you don’t read that in her memoir. So how do I convey these issues of liminality and her own struggle to be accepted in this world that sees a gradient of acceptability through your skin color and nationality? And so I have sequences about race, about passing.

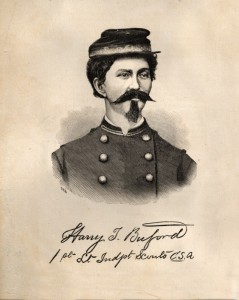

And Loreta passes in so many ways, not through gender only but also color and nationality. She chooses a man’s name to pass as a soldier, but it’s not a Hispanic man’s name. She chooses an Anglo man’s name, Harry Buford, for a reason. And so I couldn’t tell you all this in film, it would have taken most of the hour.

It would have turned it into a miniseries.

Exactly. So I have some very short sequences about race and passing, and they’re meant to invite you to understand her own conflicted emotions around her own ethnicity, her childhood, that legacy of U.S.-Mexican War. But that’s not the center of the film, but it speaks to who she is and why she feels the need to pass and to hide her ethnicity and is part of that particular journey that she makes to hide her ethnicity and her gender and eventually in the end of the film to come out and say, “I was a Spanish woman,” she would have called herself Spanish because she was part of the Spanish empire through Cuba, “and I have done this thing, but I am a true American also.”

Is that clear in her memoir?

I think it is, if you read it in its historical context. Everyone who writes in their historic moment makes assumptions about what the readers around her understand, right?

Assuming you know the assumptions, you can get a better understanding of this context?

You cannot read a 19th century memoir without understanding the history of race relations when you’re reading an ethnic writer. You can’t ignore those ethnic overtones, and they’re very much present in her memoir. And people for a long time have looked at it just as a Civil War memoir, but there is this layer of race that goes throughout the book. After all, she’s a Hispanic women entering into a conflict that is undeniably about race.

So where do Hispanics stand and why right after the U.S.-Mexican War, when America went to Mexico, do you have 10,000 Mexicans signing up to fight for both the North and the South? Is that about slavery, or is it about something else? Is it also about the legacy of what has just happened in the southwest?

Your film certainly raises a lot of questions. I take it there’s going to be a study guide because this sounds like an amazing film for use in a

classroom.

PBS Learning Media has decided to do some modules around it. And the questions will focus around assumptions of what we think of when we think of soldier. And it’s for high school, and it also focuses on the question of historical interpretation and how do we understand any historical story and how do we view it and understand it with a critical voice so that we can evaluate issues of authenticity in politics in whatever story we’re being told?

Do you think they’ll touch on the race issues?

Not directly. I think I would like to touch on the race issues, but I would have to raise more money to be able to actually create study guides around that. I’ve written stuff myself, and I hope to publish around it. But right now there’s no funds for it.

It’s certainly such a rich story to really discuss those issues, especially when you’re mixing issues of national identity and race and gender and you start to see that there are connections between all of these and that it’s not that simple.

I think that’s the case, and I think that one of the things I’m looking forward to is bringing this film to college campuses and community centers so the film can serve as a catalyst for deeper conversation about issues of race and gender, the legacy of race and gender during this most pivotal moment of American history where I think of it as that moment that we really became what we are today as Americans because we, as a country, had to grapple with the question of these old outdated ideas of racial hierarchy. And we came to a beautiful conclusion that slavery was deeply wrong.

It certainly took a long time for us to address slavery as a nation once and for all, the issue had been brewing since the colonies were first chartered.

Yes. And so the film is also a way of opening this conversation on a deeper level because we continue to have these questions of racial hierarchy. They are implicit in so many of our continuing civil rights struggles with gender and race. Right now we’re looking at complex views of stereotypes against Hispanics, the largest immigrant groups that we’ve had in modern history, triple-digit explosion of Hispanics in deep South towns with a history of racial divide against Black and white who are now faced with massive infusions of Hispanics. And they’re trying to figure out how they think about these people. And there’s been a huge increase in hate crimes against Hispanics.

The Southern Poverty Law Center has put out some very disturbing studies about that, and what do these towns think of when they see these people coming in? They think of them as people who are not part of the fabric of this nation, who have not contributed and have just swum over or crossed the border. And in fact, there’s a long history of Latinas throughout the south and the west that is not part of the narrative we tell of America’s history. Loreta’s one tiny grain of sand in this larger narrative of Hispanic participation in every aspect of our history. But it’s been an untold story, the Hispanic participation.

Right, it’s one important facet of a complex mosaic, I hope it triggers a lot of conversation and reflection.

One of the things that we haven’t talked about is the fact that Loreta had a slave. She brought a slave to bring with her to battle. And my film deals with the fact that she brought a slave with her, and eventually he runs away. She says that he runs in o the union lines by accident. But in fact, I think she lets him go.

And one of the really fascinating aspects of her story is that she’s someone who grows in consciousness from being the daughter of a plantation owner and accepting slavery. And in some ways I think her slave was a cover for her and a way for her to go accompanied into these camps with men. But she has a very complicated relationship with slavery and doesn’t seem to question it in the beginning of her memoir.

I know that by the end of her life she’s speaking out against slavery and speaking for American involvement in Cuban independence. And that is what interests me about this woman. She starts in one place, and she grows in consciousness. To me, that is a deeply American journey, and it comes out of the American experience. She’s emblematic of that.

Something that struck me about your film is the recreations do not look like the typical recreations I see in a lot of broadcast documentaries.They have this grittiness, this realness to them. And I know that you’ve made this film on a relatively low budget. So how is it that you achieve this amazing sense of realism in your recreations? Are you willing to give away a little bit of your secret sauce?

Absolutely. Before doing this film I had not done a lot of fiction work, and I was certainly very, very nervous about it. And so I watched tons of documentaries that had recreations and had a good sense of what I felt did not work in these. What I found did not work often were things like people in war or in villages — say they were supposed to be peasants or actually fighting — whose costumes looked totally pristine and who were totally clean and coifed. Oftentimes, lighting that was not beautiful feature quality lighting, there were certain things that always smacked of cheap recreation. And so I tried to avoid that, and what is fascinating is I did do some testing. And I found, in fact, for instance, that with the makeup people, we would put on a lot of dirt on people’s faces and on their clothing. But it didn’t register very easily on camera.

So I think part of the reason all these low budget documentary recreations look so pristine is that you need to have some experience, enough experience to understand what really registers on camera. And I walked into these 19th century period recreations without a real sense of the true cost of what these take.

For example, one of the things that really bowled me over was hair. When you’re talking about 19th century recreations, contemporary women’s hair is generally not long enough to create these very complicated hair styles the women wore. But you can’t just get a cheap wig. A real expensive beautiful wig that’s not a hard front, which looks very cheap and fake, can be $3,000. And so suddenly there were some costs that were terribly runaway costs, and I had to look for other ways to make up my budget.

My approach was to find historical spaces that were materially correct. The material world was actually correct in these historical spaces, and that became my set design. So I looked at many, many historical spaces to find rooms that suited what my set design was in my mind’s eye and then chose actual perspectives for the camera that I would use and then judiciously worked with prop masters to replace some of the irreplaceable furniture that I would want my actors to sit on or props that they would want to touch because the museums didn’t want me to have my actors sitting all over the place and on their treasures. And so that was one approach.

It also meant we had to have very carefully primed crews coming into these museum spaces and acting very, very respectful. And that took a lot of extra time because people in crews are used to just setting down their water or coffee on whatever table is next to them. And that might be a irreplaceable seventeenth century mahogany table. And so we had to be very vigilant about that.

Another thing that we did is we were working with armies. That means massive numbers of people, and I couldn’t afford to do that. So I also scouted actual reenactments, and there are a few shots in there when you see large numbers of armies that are actual recreations. And what we did is we got permission to shoot at the recreation, and then we put our small number of soldiers in the foreground and blocked and got only one or two takes with these armies fighting in the background.

And we had smoke machines and all of our stuff within the first 10 or 20 feet in the foreground. And then we had this massive canvas of war landscape in the background. So we did that kind of trickery in order to bring up the production value and the believability of this woman fighting in war.

However, we did do real war scenes as well. We did our own charges, and we got our own small mini armies that we did block ourselves. And I have to say for some of those camp and attack scenes, I had worked for months with many, many teams of people over the phone and meeting them individually. But the one main shooting weekend that we actually all came together and I saw all these hundreds of people around me and I was given the megaphone to actually say action, I could not get the word out. I was so overwhelmed because it was a much, much larger scale production than I had ever dared to carry out before.

But you pulled it off because it seemed like you did meticulous preproduction and planning ahead of time.

It helps to be OCD.

I’ll never forget my first film production teacher in San Francisco, Deborah Brubaker, saying, “the most important thing to remember is that all

mistakes are made in preproduction.”

It’s very, very, true because when you’re talking about one charge scene with explosions and moving cameras and teams and so on and so forth, just to carry off that one charge scene can be two hours. And so you have to choreograph far in advance. You have to have so many things in place to be able to carry that off that if you haven’t done that properly, you can waste so many thousands of dollars on that one failed production day. So you can’t mess around. And I really put a lot of eggs in that basket. I knew that it was going to be deeply, deeply expensive, and I felt that this is a Civil War film. So I had to have camp and attack scenes, and they had to come off. So I put my money in that.

I also put my money in something else, which is although we are talking about a film that uses recreations and I wanted those recreations to look believable, it’s also a film that uses experts talking and academics talking about the story. And so I used the same level of lighting, finesse, and set design for every single interview.

So every frame in that film, whether it’s documentary or dramatic, has been carefully lit and carefully worked out because you can’t have a seamless film that goes from documentary to dramatic if the lighting is shockingly different and if the settings are shockingly different. So our interviews oftentimes took four hours, not because I was talking to somebody four hours, but we were lighting and setting up for two of those hours, talking for an hour, and then breaking down because they were also carefully composed shoots.

Another thing that I played with a lot (and this was me playing with things that I know not everyone will pick up or think about) was the concept of documentary vs. dramatic film. We so often divide the two as deeply different things. We all know as documentarians that every time we turn the camera on or off, that is a choice about what you are showing. Every time we frame a frame and leave certain things out and put certain things in, that is a choice about what you are telling about that story. And we also know that, for instance, the famous Brady Civil War photographs, he would move dead bodies around on the battlefield to create his own mise-en-scène. And so I created a set of my own so-called archival photographs.

In the beginning of the film I tell everyone that there’s only one possible purported photograph of Loreta, and we’re not even sure if it’s her. So I show

that photograph, but I’m very clear that we don’t have visual material of Loreta Velazquez. So I tell everyone up front everything you’re going to see

about her is going to be a recreation. However, I use a motif of Civil War photographs of Loreta and her family throughout the film, and I recreate those in

exactly the same way Civil War photographs were created at the time.

There’s a visual language of how those photographs were created that I reuse in the Civil War photographs. And then I intercut them with actual archival

photographs of the time. And in some ways I’m inviting people to think about where is the line between a documentary archival capture of so-called

reality and a dramatic attempt at portraying reality? And are those really so sharply different?

Maybe the line between documentary and fiction doesn’t lie in the actual materials presented but somewhere else. Maybe we’ve traditionally

looked in the wrong place to find that difference between fiction and documentary.

I think that’s so. I think there’s an assumption that because something is a photograph taken at the time capturing some moment of reality that it’s

somehow truer than an artistic presentation of that event or moment. And that is, I think, a false dichotomy. When you are looking to tell stories of people

and communities that have not been deemed worthy of documentation in the past, like women, like Hispanics in the U.S. in the 19th century, then you

must look in unusual places. And sometimes you must use art to express that history.

Ken Burns could look at a history of the Civil War of the soldiers and the communities that were documented and use those. If I want to look at the history

of a cross-dressing 19th century Cuban immigrant to New Orleans, I don’t have access to massive archives of stills. There are documents, and I did go to

those archives and I spent a lot of time in those archives. There are newspaper articles. There are certain things, but I don’t have a rich trove of visual

material to use. And yet they are deeply important stories to tell. So how do I approach telling that history when I don’t have more than one possible

photograph of this woman?

But you have the stories and you have her memoir and you have various pieces of historical record. And there’s also some oral history, right?

There are diary entries, documents in the national archive, some military records, letters, her printed memoir, The Woman in Battle, and newspapers.

There are public records like marriage certificates, that kind of thing. So it’s pieced together from those little scraps. There’s another thing that I used in

my documentary very sparingly but that I felt was also deeply important to tell Loreta’s story, and that is that she has this very un-aspected picaresque tale

where so many things are happening, and she doesn’t always explain why they’re happening or how she got there. And so the story takes so many twists

and turns. I had to be very choosy about how much of her 600-page memoir I would actually put on film.

And sometimes I felt that I couldn’t necessarily tell it through a historian or through a documentary record, archival record, or through recreation. And so

sometimes I used animations that tried to speak on another level. They’re an attempt at allowing the viewer to pause and to understand her on a different

level, which is partly fantastical because they are these collages of images that we put together, and then we moved within those scenes in animation.

And then the final layer that I used was the printed text. So it was very important for me to keep reminding people of the fact that this woman had written

her story and that we use that as the inspiration to tell this film. It’s not a verbatim retelling of every word in her memoir. It is my interpretation of her life.

The first-person narrative that she tells, the voice over that she uses is based on her memoir, but it’s not verbatim. I couldn’t use her florid, over-wordy

19th century writing.

And sometimes I had to extrapolate so that a contemporary audience would understand what she’s talking about, and she didn’t say those words. So some

of the words that she verbalizes are my interpretation but there’s a lot that comes from her and there’s a primacy of text. So throughout the film you see

the actual book, the words on the book. Sometimes you see animated chapter headings from the book. And it’s a constant play with the fact that here is a

woman whose voice has been silenced, who is now telling her own story, and I’m just a vehicle for that expression.

It seems to me that in some mystical manner you were chosen to tell this story, this story found you, and some aspects of your own experience as

an immigrant who has become an American in some ways mirrors Loreta’s experience in a manner that helps you channel her so effectively.

I feel so privileged to have been able to tell this story about someone from the Latino community as a Latina woman filmmaker and as an immigrant

myself. I didn’t have a television until I was seven, and I never dreamed that I would have the privilege of telling my own stories. So to me, having grown

up watching images of my community as criminals and farm laborers, it’s amazing to be able to tell a different kind of story that is also part of the fabric

of what Latinos in America have done. And until people from those communities tell their own stories, Americans will never really understand who we

are as a nation because Latinos make up part of the fabric of this democracy, but we have been voiceless for generations.

It’s not the same thing when someone from outside the community tells a community story. It’s deeply important that someone from within the

community have that creative agency and control in speaking for that experience. So my co-producer Calvin Lindsay, who is African American, and I as a

Latina woman filmmaker needed to be the ones to tell this story about this Latina Confederate who becomes a Union spy in 19th century America.

It’s not the only way to tell this story, and I would say that it was just as important for us to have worked with Bernice Schneider, who’s an Anglo editor,

be a part of telling this story as well because America is like that. We are this nation of diverse peoples who together make up the kaleidoscope of our

society. And so we had to have this diversity of voices.

You have been working on Rebel for a long time with a lot of support along the way, can you tell me something about that?

This film would not exist if I had not had two organizations supporting me throughout the making of this film. One is Filmmakers Collaborative, of which

I’ve been a member for many years, who are an incredible community of talented filmmakers who’ve been working on this kind of film for a very long

time and who I reached out to for many years for incredible advice and emotional support.

And the other organization is NALIP, a group of Latino filmmakers, writers, directors, producers, and editors who made me feel that I was not alone in this struggle to make this film that at first no one wanted to fund and that I wasn’t sure would find a place in broadcast distribution.

Without those communities and other people supporting me, sharing their expertise, and being friends and colleagues, I would never have made this film because films are never made by just one person. I needed those communities to support me all along the way year after year to be able to finish this film.

It’s been a long journey, It’s so great to be talking with you right before the broadcast premiere of Rebel on PBS Voces.

You were of course a big part of it, both as an NALIP member and a Filmmakers Collaborative board member and a fellow Latino who was there at a critical moment when we went to the Latino Producers Academy together and you helped me to edit that fundraising trailer. And that’s also where I met Joseph Julian Gonzalez, who ended up composing the entire film. The Latino Producers Academy was a critical juncture that resulted in funding down the line thanks to the networking and mentorship I received. I learned so much in those ten days, it was an incredible experience for me that expanded my understanding of the process and support

ecosystem surrounding professional documentary. I heard that the Latino Producers Academy is currently under threat of discontinuation.

What’s the story on that?

It’s an expensive investment in filmmakers from our community. And as we know, it’s similar to Sundance, and like Sundance, those filmmakers struggling to make these independent films have to take on multi-year journeys. And so when you look at any one given year where you’ve supported a group of filmmakers and a year later only a few of those films are finished, that academy might not look successful if you’re only looking at immediate results over one year. But as we know, many films take many years.

If I recall correctly, Rebel took 12 years to make.

Yes, 12 years, I would say my having gone to the Latino Producers Academy was possibly the most important step forward in the creation of my film because it was there I made many important contacts. I was mentored by incredibly wonderful people through the Latino Producers Academy. And that helped me move forward in terms of my concept of what the film could be, in the way I pitched it, in my subsequent proposals for the film. Those are intangibles, but so important, especially given how difficult a struggle it is to create films independently.

Right, those intangibles are so difficult to measure, and yet it’s hard not to recognize the value of experiences like the Latino Producers Academy

as a beneficiary of the experience.

And so finding funding year after year for a program like that is very, very difficult. And we’ve been supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting for years, and that has directly resulted in many, many films. And now my film is finished many years later. Natalia Almada was in the first class. She won a MacArthur. Filmmakers make incredibly important connections through these academies that pay off in many different ways, and we never know how they’ll pay off. These are intangibles. But without these connections I’m not sure we would be as successful.

I partially owe the confidence of tackling my first feature project to attending the Latino Producers Academy as your editor, seeds were planted

during my time in Tucson, and though the seeds sprouted many years later, I can trace the journey back to those ten days at the Latino Producers Academy.

I think what you just said would be said by every single person that has ever been to the Latino Producers Academy.

But how do you measure that?

There’s no direct measure. There are many films that have subsequently been finished. There are many films that are still in progress.

I’m so pleased it’s happening again this year, especially since my film was among the projects chosen to participate, I’m both thrilled and

humbled and looking forward to it.

I’m mentoring this year. So I’ve gone from a member to a mentor, but who knows if it will exist next year. And that would be devastating to our community, devastating because our community of makers are not necessarily so privileged to all be able to go to NYU or UCLA Film School or even to go to film school. So workshops like the Latino Producers Academy are incredibly important. They create a social network within the film community that we might not necessarily have access to on our own.

And at the end of the day, the true value of film schools are the social connections you make. Because so many people meet their key

collaborators, writers, directors, production designers through their film school experiences.

Exactly. And we don’t necessarily have a lot of film school grads, but we have a lot of incredibly important and talented voices. So how do we support that? How do we support that when we don’t have that level of privilege in our communities? So NALIP has been that support, and we see an entire generation, an explosion of Latino filmmakers as a direct result of NALIP, and filmmakers themselves will say that often. But the funding landscape is very tough right now for everyone.

You’ve been piecing together the funding for Rebel with a little chunk here and a little chunk there, we could spend another hour and a half just

talking about how you funded this film. Do you have any funding stories to share?

As a matter of fact, at one point I had done some very expensive shooting in New Orleans based on having won a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for Humanities. Katrina happened, and they defunded me. So my bills were coming in. They had funded me about $30,000 or $40,000. I had spent that on some shoots, and they defunded me. And I was devastated, and I felt like I was probably one of the few people ever unfunded for a documentary. And honestly, I couldn’t even complain because of course Katrina had devastated lives. My loss was so minor compared to that.

How did you make up for those funds?

It took me a year to recover from the shock and the loss, and I think the year after Katrina I actually was not sure that I would continue the film. It was so devastating to have lost that funding, and it took me a year to get back up and resubmit. Two years later I got back that grant through a completely new application to the Louisiana Endowment for Humanities. So I won back that grant from scratch among other grants, but it punched me in the gut for about a year.

Wow. So one more question, what’s the most important lesson you hope that an emerging documentary filmmaker can take from your story

making Rebel? What can we learn from your experience to help make our road a little smoother?

Your story must be worthy of a very long, long journey against impossible odds. It needs to be something that goes beyond its face value of curiosity or timeliness because it could be a much longer journey than you imagine. It probably will be, and there must be some deep, deep underlying issues and messages behind that story that matter enough for you to take the journey that is making a feature length documentary film because it’s going to take every resource that you have. I often think of a professional documentary filmmaker as one that keeps hitting their head against the brick wall, expecting to eventually break through.

Most of the documentary films that I’ve been profoundly moved by are typically the result, of on the average, a decade long journey on the part

of the filmmaker. I mean, it took you twelve years to complete Rebel. It took Jane Weiner thirty-two years to finish Ricky on Leacock. It took John Marshall most of his lifetime to make A Kalahari Family, and the list goes on.

There’s a beauty to these films, and part of the depth of a film that takes that long a journey is that oftentimes you’re not working on those for all twelve years or all those decades; right? You’re going away working on some other film or doing something else and then returning to it. Every time you return to it, that film has to win its way back into your heart and mind and soul because it’s always going to be a ramp up, etc. But when you return and in the process of returning to that film and its earning its place back into your heart and mind and soul because you have to decide to recommit to it every time you return to it, you go deeper into the story.

And as a result you find another layer of what the story is really about. And I think in one sense it was a gift for me not to have received all my funding right away because by being forced to return to it, I had to reevaluate what is the kernel of my story? What is the deep meaning of my story? Why do I need to tell this? Why do I need to recommit to this? And it had to be, it had to find new layers and new interest each time. It made my story better.

Right. And those layers become evident in the final film.

Yes, hopefully.

This is a result of an extremely deep engagement with a topic on many different levels and many different perspectives, every time you change

your way of looking at something, you gain a much deeper understanding of it. A lot of documentaries made in a short period of time only take a

single path or a single perspective on a topic.

Yes. I think one of the greatest compliments I’ve ever had is after the Smithsonian premier of Rebel, someone said to me, “I loved this film, but I feel it

has so much more to say, how can I watch it again?” And that, to me, is wonderful because it’s someone acknowledging that there are many layers in this

film and for a film to be worth watching a second time, I think that’s a fabulous compliment. I was deeply humbled by that.

Tell me a little bit about the different ways I’ll be able to see the film in the near future.

Rebel will have a national PBS broadcast tonight (May 24) on the National Program Service as an hour-long special. And people should check their local

listings because sometimes local stations will show films at a different time and date. PBS World will also be showing it. Rebel will play at several times

during the Memorial Day weekend and repeat. Eventually it will be released as a DVD through PBS Home Video.

The director’s cut is 20 minutes longer, how can we see the longer version of the film?

The full-length film is starting to do festivals and get invited to screenings. The next festival will be at Frameline in San Francisco in June. I’m so

relieved that it’s done. It’s wrapped. It’s packaged. It’s about to be broadcast.

It must be good to have that excitement of the festival circuit to help counteract post-project depression, right?

Yes. Post-project depression, that’s a very good term, actually.

At the end of a major project I always feel completely lost and disoriented, like there’s this thing that’s been taking up so much of my mind, and

now all of a sudden it’s like, what do I do?

It’s my third baby. My two babies went off to college this fall, and my third baby is about to go off to the broadcast world and the festival circuit.

So you now have three children out in the world.

I’ll be an empty nester soon.

So what’s next? Have you thought about that, or are you taking a little break?

I’ve thought about, I’m deeply interested in returning to a film that I started in my 20s, which was partially based on my own experience having come to

this country as an undocumented person.

Have you started working on this project?

Yes, I started working on this, I shot footage of myself taking the oath of allegiance when I was becoming an American citizen. It was a very difficult decision to do that because you actually have to deny your allegiance to your first country. And that seemed so odd to me. When you love someone, you can love multiple people, and it doesn’t lessen your love for the other person. I was undocumented most of my childhood from when I arrived in America through when I got to college. And so today they call that a dreamer, and in my day they had not so pretty terms for it. And so my decision to become an American citizen was very wrought because I had had very difficult experiences of alienation and so forth. But also I felt deeply, deeply American.

As a matter of fact, I went to Ecuador for a year to see if I belonged there before deciding to become an American citizen. And what I found was that I did, I deeply belonged in America. And I was making films about the dirty wars, and I was making all kinds of films that were looking at American society and injustices, social injustices. I felt that to really be a part of this American democracy I needed to be a part of the solution and that part of the solution was to be a critical voice. And I could only do that safely as an American citizen.

I’m really looking forward to see what comes from that, you return to that work with so much perspective. Thank you so much for taking the

time to talk with me in depth about Rebel.

You are so welcome, I’m thrilled to be able to share.

###