“De aristócrata consentida a soldado de primera línea.”

Cuban Art News

By Nadine Covert

May 23, 2013

CUBAN NEWS – Cuban art and culture worldwide

En Español (/es/news/146-rebel-a-cuban-american-woman-in-the-u.s.civil-war-part-2-146/2830)

Rebel: A Cuban-American Woman in the U.S.Civil War, Part 2

Published: May 28, 2013

By Nadine Covert

Filmmaker María Agui Carter talks about her documentary on Loreta Velázquez.

The documentary Rebel (/news/en/139-rebel-a-cuban-american-woman-in-the-u.s.civil-war), which aired on public television last week, reveals the little-known story of Loreta Janeta Velázquez (http://en.wikipedia.org /wiki/Loreta_Janeta_Velazquez) (1842-c. 1902), the daughter of a wealthy Cuban family who was educated in New

Orleans. After the deaths of her soldier husband and young children, she disguised herself as a man and went to fight in the U.S. Civil War as a Confederate soldier. Cuban Art News asked the film’s director, María Agui Carter, to discuss her research for the documentary. (For more about the film (http://blog.americanhistory.si.edu/osaycanyousee /2013/03/part-i-rebel-loreta-janeta-velazquez-civil-war-soldier-and-spy.html), and to view the broadcast cut this month, see the PBS web site (http://video.pbs.org/video/2365009966).)

How did you first learn about Loreta? Did you think she was a fictional character or a real person?

I came across Loreta’s memoir, The Woman in Battle (http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/velazquez/menu.html), published in 1878, in the Harvard Widener Library, one of

the largest libraries in the world. But quick research on the Internet about her seemed to indicate she was a hoax. It was not until I spoke to contemporary scholars of

women and the Civil War, such as Deanne Blanton, a senior military archivist at the U.S. National Archives, and I saw the documents about Loreta housed in our

national government repositories, that I began to question why she was not part of our national history. Part of the theme of this film is an examination of the politics of memory. History is always crafted; there is never just one objective version of a story, because each story is filtered through personal and cultural and political

experience and viewpoint.

You incorporate dramatic sequences with interviews in the documentary. Was Romi Dias your first choice to play the role of Loreta?

I had asked Maria Nelson of Orpheus Casting, responsible for casting Maria Full of Grace and Real Women Have Curves, to find me the top Latina actresses in New York City. I discovered Romi Dias among them. Romi is not Cuban, but she was my top choice out of dozens of talented actors. There is only one scene in the entire film with dialogue—the climactic showdown between Loreta Velázquez and her nemesis, former Confederate General Jubal A. Early—and I needed someone who could do that well, but could also convey both the subtlety and drama as ably as a silent-film actor. Romi carried this film with such finesse.

How long did it take you to make the film, from start to finish?

I first started research on the film in 2000. I finished cutting it in 2013. But I was not working on the film that whole time. I was taking on commissioned films for PBS and cable while waiting for grants to come through. I shot the dramatic scenes in three different years, and the interviews whenever I could. Right after Hurricane Katrina [2005], I lost a major portion of my production funding from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities—after I had already spent it on the major Louisiana scenes. How could I complain when so many had lost their homes and hope during Katrina? But there were some dark moments when I wanted to give up, and it took me another year to get myself up again after losing that funding. But I reapplied and won that grant again, as well as the rest of my funding! Having to stop and start forced me to re-evaluate my film from the beginning each time. I think it’s a stronger, deeper, more nuanced film because of that.

What more can you tell us about Loreta’s family in Cuba?

According to her memoir, Loreta says her father was a native of Cartagena, Spain, a diplomat who married her French-American mother and they had their children in Madrid. Her father was appointed to an official position in Cuba and Loreta, their sixth and last child, was born “on Velaggas, near the walls in the city of Havana, on the 26th of June, 1842.” There is a calle Villegas near the old walls and that’s most likely what she was talking about—spelling in those days varied greatly, especially in American books quoting other languages. The father inherits an estate near Santiago de Cuba at Puerto de Palmas and becomes a planter in the sugar, tobacco, and coffee trade. Like many girls of her class, she was sent to be educated in New Orleans, which attracted Latin Americans to its Catholic schools. She lives with her mother’s sister in the French quarter on Rue Esplanade and is betrothed to a Spanish boy. But then she meets an American officer, who her parents do not want her to see, and eventually she elopes with him.

You note that Loreta advocated for Cuban independence. How did she do that in the U.S.?

Loreta shows up in newspapers and public records into the 20th century. She continues to reinvent herself over the years. She is a journalist, sending bylines from Latin America. She is an entrepreneur, selling shares of a failed railroad project connecting Mexico and the U.S. She remarries multiple times, and travels with her geologist husband, William Beard, on mining expeditions. And she continues her advocacy—speaking to Congress and to Cuban cigar workers in the U.S., advocating for Cuban independence.

There were many exiled Cubans working for independence in the U.S., especially in New Orleans, in cities in Florida, and in New York City. There is a Washington Post article of 1884 that puts her in New York talking to cigar workers. One of our scholars, Jesse Alemán, discovered a copy of a speech Loreta delivered to Congress, urging the U.S. to step in to help free Cuba “from the Spanish yoke” and decrying the continuing slave trade that Spain was allowing off the Cuban shores. She was an annexationist, trying to help win Cuban independence through business interests in the U.S., hoping to bring Cuba in as a new state or protectorate.

What do you know about Loreta’s descendants?

Loreta had one son, from her last marriage, who may have survived: Waldemar Beard, born in 1888. I learned of him only recently, after production was completed, when I was contacted by a woman in the U.K. named Andrene Messer, who is a descendant of the Beard family. I hope to put up online (on rebeldocumentary.com

(https://www.facebook.com/Rebel.documentary), live in August) some of my archival collection about Loreta so that others can read it, piece it together, and perhaps continue to research her. So many people are interested in genealogy and family history; I hope her descendants can be traced. That would be so exciting!

After 1902, traces of Loreta disappear. She lies in an unknown grave.

Were there other Cubans who fought in the U.S. Civil War?

There is an interesting book called Cubans in the Confederacy (http://www.amazon.com/Cubans-Confederacy-Quintero-Ambrosio-Velazquez/dp/0786409762/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1369663088&sr=1-1& keywords=cubans+in+the+confederacy), edited by Phillip Thomas Tucker, that discusses José Agustín Quintero, Ambrosio José Gonzáles, and Loreta Janeta Velázquez; it talks about some of the more well-known figures of the Civil War. There were also Cubans who fought for the Union; one of the more reknowned is Adolfo Fernández Cavada, a captain in the Union Army. He wrote a book called Libby Life, about his experiences of being captured and held in a Confederate prison in Richmond, Virginia, 1863-64. He would rise to be commander-in-chief of the Cuban armed forces fighting for independence from Spain and was executed by the Spanish army during Cuba’s Ten Year’s War.

What’s next on your agenda? Will you continue to make documentaries about the Latina experience?

Most of my work is about race and class, and the Latina experience is part of what I bring to any subject. I am working on a couple of projects. One is an exploration of the American experience of immigration and the meaning of citizenship: what does it mean beyond the accident of one’s birth? It brings in history, philosophy, literature, and art, and is partly based on my own experience having grown up as an “undocumented” child in the U.S. [born in Ecuador].

Today I would be called a “Dreamer,” who ended up going to Harvard on scholarship. But growing up I was called much less friendly things. Ten years ago I did a film called The Devil’s Music, about censorship of early jazz, and during that time I also found out a lot of information about the early Cuban roots of jazz and the connection between U.S. Spanish War military armies and early jazz. That film is also on the docket!

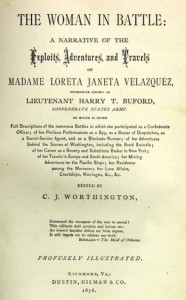

Lt. Harry T. Buford / Loreta Janeta Velázquez

Courtesy www.army.mil/hispanicamericans (http://www.army.mil/hispanicamericans)

Anything else you’d like readers of Cuban Art News to know about Rebel?

Today people may be surprised that there were Cubans, such as Loreta Velázquez, taking sides in the Civil War, particularly in the South. But to Latinos in the second half of the 19th century, the American Civil War existed in relation to larger geopolitical forces intimately tied to Spain and her colonies in the Americas. The American Civil War was preceded by the U.S.-Mexican War of the 1840s. Cuba sought its liberation shortly after the American Civil War. The U.S.-Spanish war took place in the 1890s. When the Civil War broke out, Velázquez sided with her home state of Louisiana in the Confederacy. She grew up in a New Orleans with a rich Hispanic legacy, which the South shared. The South Central Gulf States of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama are known for their French heritage and are not usually associated with the Hispanic world. But the three states all fell under Spanish rule at points between 1762 and 1813, and saw heavy immigration from

Spanish speakers.

A jewel in the Spanish empire’s crown, Cuba had intimate ties to the United States, particularly in the South. As Latin Americanist and Cuban expert Louis A. Pérez explains, in the 19th century North Americans regularly visited, and owned businesses in Cuba, and the Cuban upper classes did likewise in America, preferring to send their children to study in the United States, as Loreta Velázquez’ family chose to do. Indeed, Pérez writes, “In mid-century, Cuban trade accounted for as many U.S. merchant vessels as were engaged in the total trade with England and France.”

Cuban businessmen flourished in North America, particularly in New Orleans society. And ties to the South were strong. Prominent anti-abolitionist Southeners plotted to annex the slave-holding Spanish colony of Cuba and strongly supported Cuban independence in the 1850s. In fact, as Pérez explains, “Many Confederate officers, politicians, and planters fled to Cuba after Appomattox, from Generals John C. Breckenridge, Robert A. Toombs, to Jubal A. Early, and former Louisiana governor Thomas Overton Moore.”

For Cubans, the experience of being educated and/or living in the United States created a complex shift in their national identities during the 1800s. While Cuba was still a colony of Spain, America had gained self-rule. American technology and industry and politics represented progress. Yet the Cuban economy ran on the backs of slaves, and its closest social and economic ties were to the Southern states. As the daughter of a Spanish aristocrat who owned a plantation, it was natural for Loreta to embrace progressive ideals—such as those of women’s political and social freedom, the ideals of American democracy—and yet to endorse slavery, the source of her family’s subsistence and her country’s economy.

Loreta’s personal journey starting out as a Confederate soldier and ending as a double agent spying for the Union, and ultimately speaking out against slavery later in life, echoes a very fascinating personal growth of an immigrant who comes to embrace the American ideals of democracy.

Thank you for your time and for this fascinating documentary.

— Nadine Covert (/?ACT=19&result_path=news/authors&mbr=9)

Nadine Covert is a specialist in visual arts media with a focus on documentaries. She was for many years the Executive Director of the Educational Film Library Association (EFLA) and Director of its American Film Festival, then the major documentary competition in the U.S. She later became director of the Program for Art on Film, a joint venture of the J. Paul Getty Trust and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Covert has served on the board of the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar, and is currently a consultant to the Montreal International Festival of Films on Art (FIFA).

Follow us (http://www.facebook.com/pages/Cuban-Art-News/161562193899013) (http://www.twitter.com

/cubanartnews) (http://feeds.feedburner.com/CubanArtNewsBlog)